Books & Beer

November 1, 2021 | The Morning Blend - Milwaukee

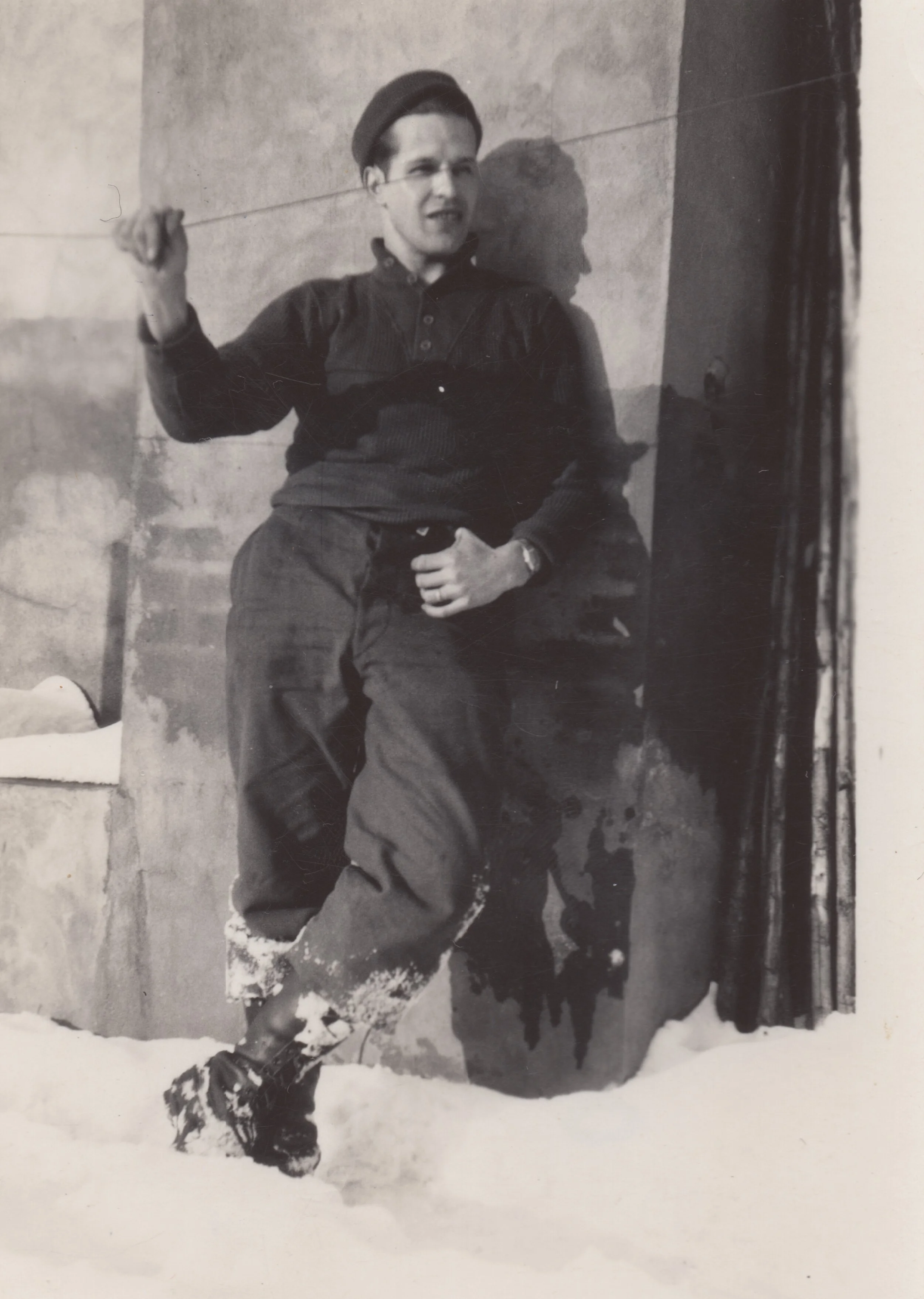

Veterans Day is November 11th. Today we meet Cedarburg resident, Louise Endres Moore. She is the author of "Alfred: The Quiet History of a World War II Infantryman."

The story is about her father. She researched the book for 17 years and spoke with veterans to uncover her father's journey. She did not know that he had been a heavy weapons machine gunner until he was 84 years old! He had only spoken about being a barber, chauffeur and translator. Louise says her father was quirky, so there are some amusing stories in his history. Today Louise will share some of the book with viewers.

Spring 2021 | On Point: The Journal of Army History

“The general public largely sees all World War II veterans through the same ‘Greatest Generation’ lens. Each veteran’s experience during the war was different. Moore goes to great lengths to emphasize that the story of the 10% that served directly in combat is unique and must be told. These men came home changed. America had changed as well, but most Americans did not understand what combat soldiers faced. They had done unspeakable things, not to be heroes, or because they reveled in combat, but because they wanted to survive and return home. Alfred Endres was a changed man who dealt with the horrors of war by keeping quiet until the death of his wife allowed some of his experience to bubble to the surface. We must thank Louise Endres Moore for writing it down.”

~ Captain Jamie McGrath, USN-Ret., Blacksburg, Virginia

Winner of American Legacy Book Awards for Biography

#1 Best Seller in Biographies of the Army | Amazon.com

Eric Hoffer Book Awards Category Finalist

IAN 2021 Book of the Year Award Finalist

Door County Library Sturgeon Bay, WI

January 14th, 2021

Virtual Author Book Talk

Watch it here

The OZAUKEE PRESS | Wisconsin

DECEMBER 23, 2020

KINDNESS IN WAR: A CHRISTMAS STORY

Louise Endres Moore of Cedarburg never set out to write a book, but the more she learned about her late father’s service in World War II, the more she realized his story had to be told.

“Alfred: The Quiet History of a World War II Infantryman” includes a heartwarming episode on Christmas Eve, 1944.

Alfred Endres and his fellow members of the U.S. Army’s 35th Division stopped at Metz, France, in between fighting in the Battle of Bulge. It was the first chance they had to bathe in two months and sleep in a cot rather than a foxhole.

Gen. George Patton’s personal order allowed the division to stay one day longer for Christmas dinner since they had been

continuously fighting on the front lines the past 162 days.

A manager of a bathhouse in Metz told the soldiers he had nothing to give his children for Christmas.

Endres and fellow soldier Ben Lane quietly delivered Army rations of fruit and chocolate to the manager’s home on Christmas Eve. They left quickly so as not to be seen by the children.

“The manager started to cry and said he would see us when we came back from the fighting,” Lane said.

Both soldiers survived the battle and returned to Metz. Charles DeWald, the bathhouse manager, gave Lane several coins and a medallion and Endres a ring.

Louise Endres Moore still has that ring, and she was able to find Lane, who lived in Hustontown, Penn. With a reunion of Lane and her father no longer possible, she came up with a different idea. She would search for the family her father helped on a long ago Christmas in France.

She remembers her father telling her the manager of the bathhouse had traveled to the United States to swim.

“I wondered how many international swimmers could there be in 1944?” she said.

Endres Moore contacted the International Swimming Hall of Fame in Florida, but it didn’t have records from that year. She was, however, given an email address for the French Swimming Federation.

Eight days after making that contact, Endres Moore received an email saying, “I think I have found our man.”

That was in 2002. She exchanged letters with DeWald’s son, Roland, who had been a professional swimmer like his father and served in the French army in Vietnam from 1954 to 1956.

He remembered the ring his father gave Endres Moore’s father, and the fruit and chocolate.

“I truly thank your dad and Ben for their kindness,” he wrote.

In talking about the story with her father, snippets of World War II memories began to emerge after his wife died and he broke a hip, forcing a move to a nursing home in Lodi

The family didn’t know much of Endres’ World War II experience. The government had sent letters to mothers and wives telling them to avoid asking questions, and Endres’ wife Louise followed the advice. But during five and a half years of his daughter’s weekly visits, her father began to open up.

Endres died in 2007, eight months after he received the French Legion of Honor for his service. A gathering of about 100 people was held at the nursing home. Endres Moore said she served Calvados, a French apple brandy her father said was so strong it could fuel jeeps.

Soon after that, Endres spoke of “dead bodies floating in the water,” his daughter said. She assumed it was a river crossing.

It turns out it probably was the beaches of Normandy, the site of D-Day. Endres said he arrived on June 7, known as D-Day Plus One.

Fort Bragg disputes that, saying since Endres arrived in Wales on June 2 he wouldn’t have had time to get there that fast. Endres Moore said she remembers her father talking about taking a train ride at night — dangerous back then since the train’s lights would have been a bombing target for Germans — and she found documentation that proves his arrival on that day was possible.

A family’s old letter said Endres arrived in France on “a Higgins boat.” When Endres Moore showed a photo of the boat to her father, he had a flashback.

She never asked another question.

But she already had uncovered enough to get her started, and she kept going, piecing together information from a document here or conversation there from across the world. What she thought would be 10 to 20 pages of information for her family turned into a 360-page book.

Research and writing didn’t come easy. Endres Moore is a retired psychology and math teacher. It helped, she said, that her parents never threw anything away.

Endres entered the Army when he was 22 after someone in the military visited the family farm. Either Endres or his brother, one year younger, would have to join. His father said he couldn’t make that decision. Endres ended up volunteering.

Endres’ family initially knew he did three things during the war. He was a barber — telling the Army he cut horses’ manes on the farm was qualification enough — a chauffeur and a translator. But he didn’t let anyone know he could speak German until later in the war for fear he’d be put in dangerous situations.

It turns out that didn’t matter since his life was always at risk on the front lines.

Endres worked with heavy weapons and was an expert shooter with a water-cooled .30-caliber machine gun.

He was once in the same room as Patton, but he told his daughter, “He wasn’t talking to me.”

Through her research, Endres Moore met Sara Rosenberry, an employee at the American embassy in Luxembourg, who came to visit her mother at the same nursing home as Endres. Rosenberry talked to Endres about the Luxembourgers’ appreciation for the American forces liberating their county.

“Dey remember?” she asked. Endres Moore said her father grew up speaking German at home and couldn’t pronounce “th.” She said that made a great impression on her father.

Endres Moore later traveled to Luxembourg and also visited Villers-La-Bonne-Eau in Belgium, where Endres’ unit replaced the one in which Joe Demler of Port Washington served. The Germans captured the unit, and

Demler, who died in February, was to become well known for appearing in a photo on the cover of Life magazine as a starved prisoner of war. The Port Washington post office is in the process of being named after

Demler, a mail carrier for many years after the war.

Endres Moore said she got to meet Demler but her father never did.

Endres’ discharge papers listed five campaigns: Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes and Central Europe.

After the war, Endres barely touched a gun. He once shot a bird off of a neighbor’s roof and was told, “No wonder we won the war.”

Endres had three sons join the military in the 1960s. One ended up going to Vietnam. His father told him not to be a hero because it wasn’t worth it.

Endres Moore said her father told her, “I wish those who get to decide could fight their own bitchin’ wars.” After 17 years of work, Endres Moore got her book published in 2019.

The Christmas story is one of which she is especially fond. “I was trying to find something good about the war,” she said.

When she got the letter from Roland, her mission was partly accomplished.

“I was teary eyed because it had worked,” she said.

Then, she had another idea. Send chocolate and fruit to her father and Lane.

The week her father got the fruit and chocolate, it was Endres Moore’s out-of-state siblings turn to visit. They said he didn’t say anything about it, but Endres Moore said she knows he felt something.

“I think he did. I think here,” she said, pointing to her heart.

Milwaukee journal sentinel

June 21, 2020

Thinking of his baby girl

Seventy-five years ago, Alfred Endres celebrated his first Father's Day the month after the war in Europe had finally ended. But it would still be several months before the Wisconsin farmer would return home to hold his daughter Eileen.

Eileen Waldow was born Sept. 13, 1944, some 13 months after her parents married. Endres got the happy news two weeks after she was born, while his unit in the 320th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division was pinned down.

He was 26 and soon picked up the nickname "Hot Papa," said his daughter Louise Endres Moore, who wrote a book about her father's wartime experience, "Alfred: The Quiet History of a World War II Infantryman."

Endres survived several campaigns following the D-Day invasion and push across Europe to defeat Germany.

Like many World War II veterans, Endres didn't talk about his experience until much later in life and his family accepted his answer when asked what he did in the war — chauffeur, barber, translator. It wasn't until a few years before Endres died in 2007 that they learned he was a machine gunner who had seen heavy fighting.

"He went into the Battle of the Bulge, from what I understand, never thinking he would meet me," Waldow said in a phone interview from her Colorado home. "The statistics they were given were pretty gruesome."

Endres met his wife, Louise, at a wedding dance when they were teens growing up near Lodi and Cross Plains. After they married in the summer of 1943, Louise traveled to California with him while he trained for war. Among their group of eight couples in the same Army outfit, three of the husbands would die in battle and never get to meet their children, said Moore.

Later in life, Endres told Waldow "I didn't think it would take so long for me to see you," she recalled. "I don't know how he turned out to be such a stable, loving man. He must have had a compartment that he put the war away."

When he returned home, he raised a family that would eventually include eight children on a dairy farm in Lodi. Father's Day was usually celebrated with a special meal and a trip to church for Sunday Mass. But other than that, the holiday was not a big deal because Endres was busy being a farmer, husband and dad.

"We would give him a (Father's Day) card and he would say 'Thanks, it's very nice. Now put it away and give it to me next year,’ ” remembered Waldow. "I don't think we ever did but ... he thought it was an unnecessary expense."

After their mother died in 2001, family members found and read letters he sent home from World War II that had been kept in his Army trunk. Among the cards and letters was a note Endres wrote in pencil on Dec. 9, 1944.

The Battle of the Bulge, Hitler's last-ditch effort to stop Allied troops, would start one week later and Endres' unit would be in the thick of it. American casualties in the Bulge totaled almost 90,000.

Endres was thinking of his baby girl and his wife at home and longing to be with them for the holidays.

He wrote: If we're not together for Xmas let's make the best of it like we have been and we got our happy future to look forward to, so here's wishing you & Eileen a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

Love, Daddy

Meg Jones is at home virtually anywhere in Wisconsin, reporting on the character and characters of her home state for the Journal Sentinel and Sentinel since 1993. She was part of a team named a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2003 for coverage of chronic wasting disease in the states deer herd. A UW-Madison graduate and former member of the Badger band and women's crew team, the Rhinelander native has a passion for covering weather and military affairs. Since the war on terror started after 9/11, she has made eight trips overseas to cover Wisconsin troops in battle four trips to Iraq and four to Afghanistan.

Email her at meg.jones@jrn.com; follow her on Twitter: @MegJonesJS.

the capital times | madison, wisconsin

June 21, 2020

Louise endres moore: honors families who lost their fathers in world war ii

Seventy-five years ago, my father survived World War II to celebrate his first Father’s Day while still in Europe in 1945. By that time, I believe he was finally confident that he would make it home to Wisconsin to meet his first-born daughter. He had learned of her arrival about two weeks after her birth. On the day he heard the news, his 1st Battalion within the 35th Infantry Division under Patton had been surrounded on three sides by attacking Germans, who were some of the best troops of Field Marshall Runstedt.

Six decades later at the Good Samaritan Nursing Home in Lodi, I asked my dad about the birth of my oldest sister Eileen, “What were you doing at the time?” He responded far too quickly, “I don’t know.”

I suspect he knew exactly what he was doing, but whatever his behavior was, it would never make sense to anyone who expected to live to see the next day. The day after he learned he was a father, he pulled himself together and wrote a letter to “My Darling Wife and Eileen.”

My father was fortunate because he would, in fact, eventually return to Wisconsin and meet his 13-month-old daughter. Out of the group of his eight buddies training for the infantry, three did not return to their wives and first-born children. In total, there were 183,000 “orphans” among the soldiers who served during World War II, children who would never celebrate any special day with their fathers.

During our recent quarantine, many people used their extra time to purge their homes of unnecessary items. If my parents had been more diligent on that front while we were growing up, I would never have found letters and war remnants that allowed me to piece together my father’s hellish journey through World War II. Some years ago, we discovered a heartbreaking letter and birth announcement in my parents’ safe about a soldier, Eddie, who trained with my father. The discovery of that 1944 letter allowed me to find the “baby” in the birth announcement because of their distinctive family name and the detailed future plans found in the letter about moving from the state of Oregon to New York. The baby’s mother, Sophia, wrote to my mother:

It is with a heavy heart I write you this. We all had such grand plans for when this war is over and how happy we would be. But for some of us, and I guess I am not alone in it for it is happening all over the world, and I know Eddie would have been so proud and happy had he had but the chance to know of his baby girl. But maybe it was not meant to be that way. I received a telegram from the war department the morning before I left the hospital that my darling had been killed in action September 17. If only he could have known. I am sure he is watching over us now…"

Another of my dad’s training buddies, Frank, was unfortunately, if not criminally, shot two days before the war ended in Europe. Just last month, 75 years and 3 weeks later, I discovered Frank’s family because of a 1998 Christmas letter that had not yet been recycled. On the backside of the enclosed photos, each person was clearly identified, and a four-page letter included the names of several small towns in New York.

I had passively taken that stash of 1998 Christmas cards home with me from our family farm. Then just four days later, I was speaking with Frank’s grateful granddaughter. Her grandparents and mother, an only child, had all passed away, which is why I never expected to connect with that family after I published my book. This granddaughter was so appreciative of the letter her grandmother Margaret had written for me. It described in detail how Margaret received the news of Frank’s death. Margaret expected the telegram to provide information about her husband’s return to the United States in October, as that is what Frank was telling her would happen. It was minutes before noon, and she was about to cook macaroni. The telegram began, “We regret…” Frank Poelluci had died the day before his wife’s first Mother’s Day.

Now, 75 years after my dad’s first Father’s Day in Europe, as one of eight children, I am grateful to be here at all. I am grateful to have lived within the loving, quiet, amusing presence of my father, Alfred, until his death at the age of 89.

Yet, I am keenly aware of all those orphans of war who were cheated out of that opportunity to personally know their fathers beyond the stories they may have heard or which may have been too painful to tell. May we honor those fathers and their families as well.

duck town podcast | lodi library

Author Talk with Louise Endres Moore

May 20, 2020 Waunakee Library, Waunakee, WI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1OmTWONQMU

March 6, 2020 Village Booksmith, Baraboo, WI

https://www.wpr.org/alfred-author-louise-endres-moore

November 12, 2019 Lodi Enterprise, Lodi, WI

https://www.hngnews.com/lodi_enterprise/article_8d7d2206-ff09-5639-852f-34f026438eb2.html

June 6, 2019 TMJ4 Television, Milwaukee, WI

https://www.tmj4.com/news/local-news/cedarburg-woman-writes-book-on-fathers-secret-world-war-ii-service-75-years-after-d-day-invasion